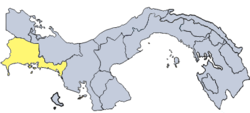

One trip to one part of one county’s coffee growing region is limited information to work with. Nonetheless, my recent visit to the western highlands of Panama was an eye-opener, replacing a mental image based on a great deal of reading and examining photographs with the reality on the ground. I’d like to share some of what I learned.

First, a little overview of the entire landscape. The highest point in Panama is in the western highlands: Volcan Baru, at nearly 3500 m (almost 12000 ft). The town of Volcan is on one flank of the volcano, Boquete is on the other. These are Panama’s major coffee-growing areas, some of the most important in the world. Coffee is not the exclusive crop, however. Many cool season crops are grown here. We were on the Volcan side, where cabbage, lettuce, and onions were common, as well as dairy farms. Small farms and plots were everywhere, creeping up the flanks of the mountains. Most were not large, and from what we could gather by observing harvesting and taking crops to central depots, tended by one to several families. We have urban sprawl. They have a sort of agricultural sprawl.

Definitions of shade-grown coffee describe various systems that go from very rustic (coffee in a forest) to sun coffee (plots of coffee with no shade trees). I talk about this continuum in my introductory post “What is shade-grown coffee” and provide a graphic in a later post on shade certification criteria. Coming from an industrialized country with industrialized agriculture, where even small garden plots nearly always follow an orderly, genteel, Euro-centric plan, I really didn’t consider how “messy” agrosystems are in Latin America. We spent a lot of time on one coffee finca, lesser amounts in two others, and passed through a number of others. The various levels of shade management are present, but they can be difficult to categorize as they are often interspersed with each other and other types of land use (crops, livestock, homesteads).

We spent two half-days at Finca Hartmann, a very eco-friendly farm near Santa Clara. It is in two sections: the lower Palo Verde section (1200-1300m), and the higher-altitude Ojo de Agua section (1500+ m), which is directly adjacent to the La Amistad International Park. The property (aside from housing and other human infastructure) is a mix of remnant and regenerating forest, pasture, and coffee. Coffee occurs in plots ranging from 1 to 15 ha, and itself grows intermixed with native vegetation and/or crops such as citrus and bananas. This photo shows some fairly young coffee (probably 2-5 years old; the Hartmann’s are in the process of replanting much of the farm which was established in the 1950s) at Palo Verde, shaded by citrus, castor, and native trees. We had a large mixed flock of birds here, including forest birds such as White-ruffed Manakin and Bay-headed Tanager.

In another area in Palo Verde, older coffee trees are growing amid a mid-story of bananas, and an open canopy of tall native trees, encrusted with many ephiphytes — which are very important to biodiversity in tropical agrosystems.

The Hartmann’s have preserved a lot of forest on their land. Below, my husband consults a field guide in a beautiful forested patch along a stream. There is extensive old forest at Ojo de Agua which many researchers have used to study forest and shade coffee ecosystems.

Nearly 300 species of birds have been recorded at Finca Hartmann, as well as 62 mammal species and hundreds of other organisms. Patriarch Ratibor Hartmann is a devoted naturalist, and visitors can examine some carefully-curated collections he has made on the farm. We photographed many insects ourselves. One was a damselfly that had only been described about 30 years ago, and had never been photographed, according to an expert back here in the states.

Nearly 300 species of birds have been recorded at Finca Hartmann, as well as 62 mammal species and hundreds of other organisms. Patriarch Ratibor Hartmann is a devoted naturalist, and visitors can examine some carefully-curated collections he has made on the farm. We photographed many insects ourselves. One was a damselfly that had only been described about 30 years ago, and had never been photographed, according to an expert back here in the states.

Other insects were just stunning, such as this metalmark, Mesosemia asa. Although we really only explored for 6 or 7 hours over the two days, were working without a guide, and spent equal amounts of time looking at insects, we observed nearly 80 species of birds at Finca Hartmann.

Other insects were just stunning, such as this metalmark, Mesosemia asa. Although we really only explored for 6 or 7 hours over the two days, were working without a guide, and spent equal amounts of time looking at insects, we observed nearly 80 species of birds at Finca Hartmann.

Other farms in the region were in contrast with Finca Hartmann. The photo below is from Finca Florentina near Paso Ancho, a large plantation that has been a source of beans for Starbucks. This farm also had patches of forest, but coffee typically grew in larger plots than at Finca Hartmann.

Still at Finca Florentina, an even larger plot of coffee, with sparser large trees. This area had a lot of non-native eucalyptus trees. We wandered through these areas for several hours, and saw far fewer species of birds and insects. Many were more common species typical of open areas, such as various species of grassquits, or the ubiquitous Rufous-collared Sparrow.

And along a road near Santa Clara, were big areas of sun coffee. These farms are likely owned by or sell their beans to the large Cafe Duran, which is a common brand in Panama. Their mill was nearby.

None of the coffee growing areas we saw came close to matching the structural complexity of native forest, a characteristic that is highly important to biodiversity. Nonetheless, it was clear that birds and other fauna used coffee growing areas that were integrated with or close to native vegetation.

This gave me a great deal of insight into the issue of shade certification, and I will talk about that in my next post (Why certifying shade coffee is so complex).