Is coffee really at risk of extinction?

Recently, a paper was published in the peer-reviewed, open-access journal, PLoS ONE: “The impact of climate change on indigenous arabica coffee (Coffea arabica): predicting future trends and identifying priorities.”

It specifically looked at wild, endemic populations of Coffea arabica in Ethiopia (and a few points in nearby areas). In a nutshell, the authors created computer models using known localities, environmental conditions, and various climate change scenarios to predict current and future distribution of these populations. The models determined a reduction (ranging from very worrisome to nearly complete) in suitable locations in this region by 2080. This is no surprise. I’m not sure I’ve seen any models that do not show some impact on the ranges (whether expansions, contractions, or shifts) of plants and animals under any accepted climate change scenarios. And we all know coffee is a very climate-sensitive species, especially arabica coffee.

It is a big leap to go from what this paper actually examined and concluded to the shrill, frantic headlines and stories pumped out by mainstream media. For instance, under the headline So Long, Joe? World Coffee Supply Could Be Threatened By Climate Change, US News and World Reports declared “Nearly 100 percent of the world’s Arabica coffee growing regions could become unsuitable for the plant by 2080.” This is way off base, given the study was only looking at wild arabica in the vicinity of southwest Ethiopia. The article also stated that “If Arabica becomes impossible to raise in its native areas, it could wreak havoc on the economies of the mainly third-world countries in which it grows,” which is ridiculous considering that coffee is already grown on millions of acres in dozens of countries around the world where it is not native. Likewise, Salon.com made the even more extreme statement, “By the end of this century, climate change could wipe out nearly all the world’s coffee” in their piece, Coffee beans at risk of extinction.

I could cite more hand-wringing examples of failure by news outlets to make an honest effort at reporting what this paper really said, but you get the gist. As a scientist, journalist, editor, and world citizen, this lack of accuracy disgusts me. First, there is no excuse for it; the paper is open-access and anyone can read it for themselves! Apparently, this dismal reporting stems from incomprehension, laziness, and/or incompetance on the part of writers and their editors, as well as a disregard for actually informing the public in favor of profit for the news outlet via sensationalism.

If you’ve read this far and want a more nuanced analysis of the paper, I’ll give a few of my thoughts.

I thought the paper was thorough and well-conceived. The bioclimatic modelling used is pretty standard for looking at the distribution of species under future climate change situations. Computer models, of course, are as robust as the data one feeds into them. In this paper, the bulk of the data used to model current distribution was based on unpublished field work done by one of the authors; the rest was from herbarium specimens or literature reports, some dating back to 1941. Ergo, it is technically not possible to evaluate the quality of this data. The climate data emphasizes factors like temperature, rainfall, and seasonality. These are all critical for coffee growing, but the models did not integrate other important environmental influences on coffee production such as soil types, microhabitats, and ecological processes, and the authors acknowledge those shortcomings.

The results and discussion provided didn’t stray far beyond these limitations and delivered on the authors intended goals: to identify conservation, monitoring, and research needs for wild, native Coffea arabica. It established baseline data to help assess future impacts of climate change on these populations, having identified suitable localities for them.

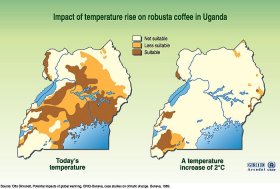

Two paragraphs in the discussion are devoted to the implications of the findings for cultivated arabica coffee, and they are also presumed to be negative. Does this mean the news headlines, while not the subject of the actual paper, are true? Not exactly. The authors note that optimum cultivation requirements for arabica coffee will likely become harder to achieve in the face of climate change, productivity will probably be reduced, and more intense management (especially irrigation) will be needed.

Is the potential loss of genetic resources in these populations something to worry about? In their article Climate change threatens sweet smell of morning coffee, Reuters took a stab at trying to interpret what the paper had to say by writing, “Although commercial coffee growers would still be able to cultivate crops in plantations designed with the right conditions, experts say the loss of wild arabica, which has greater genetic diversity, would make it harder for plantations to survive long-term and beat threats like pests and disease.” Indeed, a reason the authors focused on wild populations of arabica in their native range was that their genes may be valuable for breeding disease and pest resistance and climate resilience into commercially grown coffee. While this is logical, and maybe even likely, the paper did not provide detail on the genetic diversity, number of unique arabica strains, or other features of the coffee being mapped and modelled. In fact, the authors noted that genetic variation in wild arabica still needed to be assessed. Further, other more tolerant species of coffee (primarily Coffea canephora, robusta, and its hybrids) are being used in breeding programs today and probably hold the best hope for resilience in commercial coffee. (This is not to discount the importance of preserving these populations; I’m a strong believer that genetic biodiversity should be preserved regardless of it’s commercial value.)

One point was made in the paper that I thought was not given enough emphasis. The biggest driver of the loss of wild coffee populations has been and is deforestation and land conversion, which themselves exacerbate climate change. We can sit on our hands and watch one of the models in this paper play itself out, with what the authors term as “profoundly negative influence” on coffee. Or we can encourage the production (and consumption) of coffee grown in an ecologically-sustainable manner, using carbon-capturing shade trees and sensible agroforesty techniques — and reward farmers for their troubles by paying more for eco-friendly coffee. The press could make a real contribution by informing the public on the issues surrounding the sustainability of one of the world’s most popular beverages, rather than thoughtlessly spew out faulty proclamations with little basis in fact and no call to action.

More of my posts on coffee and climate change here.

Davis AP, Gole TW, Baena S, & Moat J (2012). The Impact of Climate Change on Indigenous Arabica Coffee (Coffea arabica): Predicting Future Trends and Identifying Priorities. PloS one, 7 (11) PMID: 23144840

(Updated) Finca Platanillo in San Marcos, western Guatemala is the first coffee farm to be verified by Rainforest Alliance (RA) for compliance with the

(Updated) Finca Platanillo in San Marcos, western Guatemala is the first coffee farm to be verified by Rainforest Alliance (RA) for compliance with the  I

I  Verification occurs if farms comply with 80% of the 15 voluntary criteria of the module. Failure doesn’t effect the compliance score of regular RA certification. Farms can have the Climate Module audit done at the same time as their regular audit for RA certification; thus, it incurs no additional costs.

Verification occurs if farms comply with 80% of the 15 voluntary criteria of the module. Failure doesn’t effect the compliance score of regular RA certification. Farms can have the Climate Module audit done at the same time as their regular audit for RA certification; thus, it incurs no additional costs.